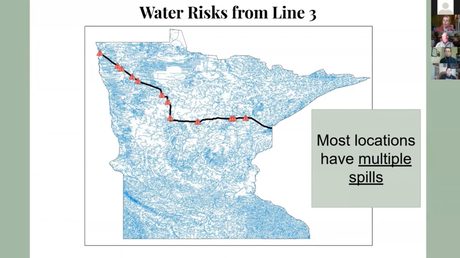

This post was written by Matt Doll with the Minnesota Environmental Partnership* on Sept 25, 2021. Line 3 is an Enbridge pipeline project taking tar sands oil from Alberta to Superior, Wisconsin. Opposition to this pipeline has been strong, but the project continues to move to completion. There have been a number of spills of drilling fluid and incidents where construction endangered ground water and fens in the area. On Thursday (Sept. 24), MEP sponsored an online presentation, “Understanding the Line 3 Aquifer Breach and Spills,” in which geologists and Indigenous pipeline resisters shared information on the impacts that construction of the Line 3 oil pipeline is already having on our waters and ecosystems. Though science has predicted that Line 3 will harm our climate and pose a threat to Northern Minnesota waters, the presenters painted a disturbing picture of the damage that Enbridge has already inflicted on land and groundwater. The video is now available on MEP’s YouTube channel. Our first presenters were geologists Jeff Broberg and Dr. Laura Triplett, who began by explaining how Enbridge’s digging of a deep trench near the Clearbrook Terminal caused an aquifer breach. Earlier this year, the crews sunk sheet pilings - stabilizing structures that prevent trench collapse - deep into the earth while operating in the trench for the new pipeline. Those pilings pierced into the waters of the aquifer below the layers of earth. When the pilings were removed, water gushed upward, forming an eruption of quicksand that resembled boiling water. The result of this breach, beyond the release of water into the trench, is that nearby ecosystems are harmed, specifically a variety of wetlands known as “calcareous fens.” These fens are highly biodiverse and sequester large amounts of carbon, but are dependent on water springing up from the aquifer. The loss of their water can dry them out, which is why permitting for this pipeline included measures meant to protect the fens. “What we have here is a cascading series of failures,” said Broberg, “that started with the design and permitting.” Originally, he said, Enbridge’s plans presented to regulators indicated they would dig a trench only eight feet deep to protect the fens, but crews ended up digging eighteen feet deep instead to avoid the company’s other pipelines. The aquifer breach is estimated to have been releasing up to 100,000 gallons of water into the trench every day. The breach began January 21. Over 25 million gallons have been lost. The DNR only ordered Enbridge to fix it last week, “There was a failure of the backstop that we rely on with our regulatory agency,” said Triplett. “I don’t think the system worked.” The DNR also told Enbridge to fund an escrow with $2.75 million for the restoration of damage to the calcareous fens sensitive ecosystems that have been risked. Understanding the damage to the fens may take years to uncover. The company has also been assessed $300,000 for the water from the aquifer that has already been (25 million gallons) and will be lost by the time the aquifer is repaired, if that is even possible. This amounts to about 1 cent a gallon for this water. The DNR has also assessed a forgivable $20,000 administrative penalty order, the most allowed by state law. These do not amount to penalties or deterrence for future law violations for a company with almost $30 billion in income for the year 2020. The presentation continued with Dawn Goodwin, an Indigenous organizer with the Indigenous Environmental Network, co-founder of the RISE Coalition, and a resident of the Clearbrook area. She described how she and other Indigenous pipeline resisters have monitored Line 3 construction in treaty lands, lands on which the Ojibwe have the guaranteed right to gather resources like wild rice and fish. They have uncovered and documented spills along the line known as “frac-outs,” in which drilling fluid used in construction surges into low-pressure spaces during excavation, resulting in chemical pollution and disrupting the local hydrology. “This is a pattern of Enbridge rushing, not reporting, and being so slow and not transparent,” said Goodwin. Like the aquifer breach, these frac-outs often go unnoticed by state authorities, and result in harm to land, water, and wildlife. The effects of this pipeline construction, coupled with climate change effects like this year’s drought, gravely threaten the culture and livelihoods of the Ojibwe. Ron Turney, a member of the White Earth Nation and of the Indigenous Environmental Network’s media team, showed his own drone footage that has helped to identify these frac-outs, which have occurred on tributaries of the Mississippi (Turney’s section begins around 47:45 in the video). He described how Indigenous monitors identified these issues, raised them publicly, and were wrongly accused by the Pollution Control Agency of spreading disinformation. “But we have the evidence,” Turney said. “They can’t hide this from us - they can’t hide it from the public.” 100 people, including journalists and legislators, joined us for the meeting, and the most common question asked was, “What should we do?” The presenters’ responses varied in details, but they all focused on the core issue: Enbridge has repeatedly failed or refused to protect Minnesota’s environment, and our state agencies have failed to hold the company accountable. Jeff Broberg said, “We need our state elected officials to make the calls. We need our State Representatives and Senators and Governor Walz and Senator Klobuchar and Smith to call President Biden: tell him that these water permits should be abandoned.” Both President Biden and Governor Walz have the power to halt this pipeline if they choose. Between these harms to state lands and waters, the associated cover-ups, and the catastrophic climate impacts of this pipeline, they have nothing but good reasons to do so. We've written about this project on the LWV UMRR blog previously - click here for past posts. *The League of Women Voters Minnesota is a member of the MEP, and LWV UMRR participates with MEP through that connection.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

| LWV Upper Mississippi River Region | UMRR blog |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed