|

In a counterpoint to the Governor’s talk at the January 27 Water Summit, retired Cargill CEO Greg Page talked about how the measures that have been undertaken so far in Minnesota fall far short of the mark. For example, the $500million in CREP funding will pay to take out of production about .33% of all farmland in Minnesota. Assuming the land that’s retired is the most polluting .33%, this will reduce the nutrient load to the Mississippi by about 1%. Our goal is 40% reduction, so much more is needed. Farmland retirement is not a practical answer for most of the problem; we need to find ways to farm that are much more protective. Page’s talk was philosophical in nature, saying that change can happen in one of three ways – through edict, order or regulation; through incentives; or through “collective voluntary responses to a shared threat”. He argued that the agriculture community needs to exhibit share values of water protection, and that if significant changes in how food is grown are not forthcoming, there will be more edicts to order change. These changes are beginning now, and the effects are spreading. Through practices like precision agriculture, farmers use less nitrogen now per unit of corn produced than they did a generation ago. A “wicked problem’, said Page, is a problem where there’s no single solution that is more virtuous in every dimension. Each way we try to solve it, there will be trade-offs. Food and energy production are vital to our world today. The problem of nutrient pollution cannot be solved by vehement single issue solutions, he says; we must find a way to raise the fertility of the land being farmed while protecting our water resources.

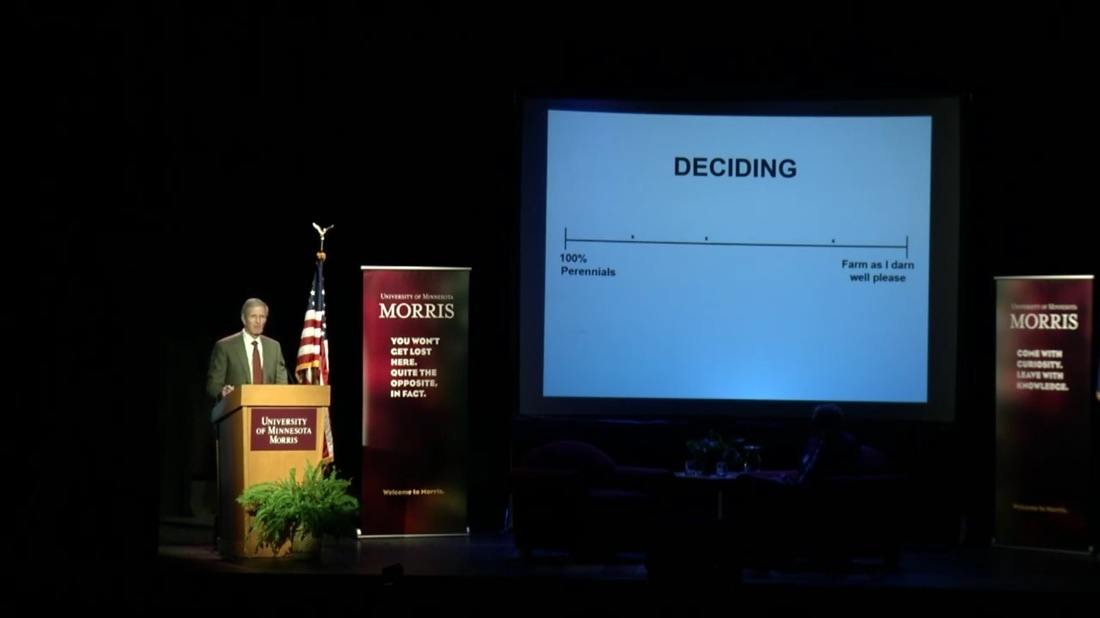

There have already been changes in Minnesota farming that contribute to the problem – increasing rainfall (both in volume and intensity), fewer animals on the landscape meaning less pasture and more row crops, and increasing intensity of plantings. (Read about the green revolution that was fostered at the University of Minnesota.) At the same time, techniques like precision agriculture, where sophisticated GPS systems control the rate of fertilizer application to match what’s precisely needed by the crop at any given point in the field, are improving the efficiency of fertilizer use. We need to find the point where production is optimized for nutrient use; this will include improving soil health to retain more water. Page pointed out that there are obstacles to making the needed changes. The first obstacle is ‘single constituency advocates’, those who want to seek a solution to a single aspect of this wicked problem rather than to optimize for the best fit answer for all aspects. Another problem is that people have limited awareness of the trade-offs involved on a global scale. The cost of the alternatives needs to be quantified to be understood. He showed a graphic of a ‘continuum’ where at the left end all farmland was returned to 100% perennials and at the other there was no concern for the environmental impacts of farming practices. There is a point somewhere between these two ends where we can optimize both agricultural production and environmental protection. It will take frank and open discussions between farmers, consumers, environmentalists and government to find that point and do what it takes to make it a reality. We need to build trust and lower resistance to change for this to be successful. We have found the shared threat, now we need to get going on the collective voluntary responses to solve it.

1 Comment

|

| LWV Upper Mississippi River Region | UMRR blog |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed