|

The Illinois Extension Service is offering online and hybrid classes on a variety of topics like gardening, invasive insects and night skies. Many fun offerings here to make the winter go faster! HOME, COMMUNITY, COMMERCIAL HORTICULTURE

Jan. 23, 1:30 PM: Native Seed Starting for Spring Planting | Four Seasons Gardening Online Native plants are adapted to grow and survive in all types of Illinois weather, knowing how they grow will help growers learn how to start native seeds for their garden. Winter sowing is a technique used to help people save money and easily grow plants. Learn techniques to grow even some of the trickiest plants with limited space and no specialized equipment. Contact: Gemini Bhalsod Feb. 13, 1:30 PM: Insects to Know: Spotted Lanternfly and Periodical Cicadas | Four Seasons Gardening Online In 2023, the first spotted lanternfly in Illinois was identified in Cook County. In spring 2024, a large brood of periodical cicadas is set to emerge in Northern Illinois, making it a big year for insects. Learn about the biology of these insects and what their arrival means for gardeners and farmers. Contact: Gemini Bhalsod Feb. 27 - March 28: Growing Great Vegetables Online Dig in with confidence this spring with Growing Great Vegetables, a five-week webinar series that will cover how to grow a vegetable garden from seed to harvest. Contact: Ken Johnson

Online Discover the power of rain gardens, which act as nature’s filter by slowing stormwater runoff, reducing soil erosion, and relieving strain on stormwater systems. Gain insights into the principles of rain garden construction and design, ensuring gardens not only enhance the beauty of a space but also contribute to the health of the environment. Contact: Gemini Bhalsod ENVIRONMENT Jan. 11, 1 PM: New Invaders: Spotted Lanternfly | Everyday Environment Webinar Series Online Help keep invasives out of Illinois. Spotted lanternfly is the newest “unwanted” invasive pest in Illinois. Learn how to identify and report this invasive insect as well as how to manage it and prevent further spread. Tricia Bethke from The Morton Arboretum will explore why monitoring for spotted lanternflies in winter is important and how you can help report invasives with early detection and rapid response. Contact: Erin Garrett Jan. 25, 9 AM: 2024 Illinois Nutrient Loss Reduction Strategy Partnership Conference In-Person at Illinois Department of Agriculture Building, Springfield, or Online The 2024 Illinois Nutrient Loss Reduction Strategy, NLRS, Partnership Conference presents the latest updates to the NLRS and is open to Policy Working Group members, stakeholders, and the general public who are interested in the topic of reducing nutrient loss in Illinois. This includes those involved in the agriculture, point-source, and urban stormwater sectors. Available in person or online for attendees. Contacts: Rachel Curry, Joan Cox, or C. Eliana Brown Feb. 8, 1 PM: Empower Illinois: Strategies to Reduce Nutrient Pollution and Protect Waterways | Everyday Environment Online Everyone has a role in preventing nutrient loss. The lakes, streams, and rivers of Illinois are vital for drinking water, wildlife, recreation, fishing, and industry, and everyone has a role in safeguarding water here and downstream. Explore what nutrient pollution is by learning about the Illinois Nutrient Loss Reduction Strategy, NLRS, and how it works to reduce nutrient pollution from nitrogen and phosphorus. Contacts: Rachel Curry, Joan Cox, or C. Eliana Brown March 14, 1 PM: Protect Our Dark Skies: How to Limit Light Pollution | Everyday Environment Online Starry nights are only possible when we turn out the lights. The sky is a natural wonder that unites everyone in Illinois, our nation, and the world. The Milky Way, the orange glow of Jupiter, the constellations Orion, and the Big Dipper all capture our attention and fill us with awe. However, for many of us, the sky is not dark enough to see more than just a few stars. Explore how to take a closer look around your home and community to assess night light conditions and simple ways you can help keep our night skies dark. Contact: Amy Lefringhouse FORESTRY AND TREES Jan. 22 - Feb. 26, 8:30 AM: Tree Care Workshops | Community Tree Care Series Multiple Dates, Locations Routine maintenance and proper care techniques contribute to a longer, healthier tree life. Each workshop location session includes hands-on training during the time of year when tree care is applicable to apply tree care skills, discuss local issues, identify needs in individual communities, and provide opportunities to learn more. Exact locations will be available closer to event dates and subject to change due to winter weather instances. Sessions are the same and repeated in multiple locations. Contact: Sarah Vogel Jan. 22: Mattoon Feb. 5: Decatur Feb. 26: Milan Jan. 27, 9 AM: Winter Trails and Naturalist Tales Tortenson's Education Center, Pecatonica Embrace winter's beauty through outdoor exploration and indoor inspiration with University of Illinois Extension. Tour about and take in the sights and sounds of nature. Contact: Tammy Bene March 6, 8 AM: Gateway Green Conference 2024 Gateway Convention Center, Collinsville Natural resource industry professionals face the vital task of responsibly caring for our communities' valuable environmental resources. Evolving research and environmental changes make it more important than ever to explore responsible stewardship practices. The conference provides a platform for sharing new ideas and research-based information as experts delve into three vital tracks: building sustainable landscapes, conservation stewardship, and tree care. Contact: Sarah Ruth Eight years ago, St, Cloud (MN) Mayor Dave Kleis set a goal for City operations to be carbon neutral by 2030, not including energy generated by the city's hydropower dam on the Mississippi. The city met the goal of carbon neutrality in 2020 - ten years ahead of plan. When taking into account the hydro facility, the city now produces three times as much energy as it uses as a municipality — saving about $1.5 million from their annual budget. The City's new goal is that by 2028 the entire St. Cloud community is carbon neutral for its electrical use, and by 2038 will be carbon neutral for electrical, building heat and transportation. As part of meeting this goal, the City of St. Cloud is now pursuing a course that could lead to their city operations to being carbon negative - taking in more carbon than they emit. They are integrating treatment of their wastewater, the use of solar energy to power their services and the recovery of biogas and fertilizer. The treatment center is also poised to be the first wastewater facility in the world to use all end products on-site from the electrolysis process, including: producing green hydrogen, green oxygen and waste heat, fuel and pure oxygen on-site, as well as run the first program in the country to capture carbon from exhaust and be able to sell the end product for building materials.

The webinar was recorded - click the video link above to watch it on the LWV UMRR YouTube channel.  About Tracy Hodel: Tracy Hodel earned a degree in aquatic biology from St. Cloud State University in 2000. She began her career with the city in 2001 as a laboratory technician. She was promoted to utilities water quality coordinator in 2003 and to assistant public utilities director in 2006. In November of 2019, Tracy was appointed St. Cloud’s Public Services Director. Tracy is certified in water and wastewater operations; she is also certified in Envision Sustainability, which focuses on implementing sustainability in infrastructure projects. Providing innovative, high quality, cost-effective public services to the City of St. Cloud’s residents and customers is a key driver for Tracy’s current role as Public Services Director for the City of St. Cloud. In recent years, the City of St. Cloud has taken a national and global leadership role in its sustainability efforts due to City staff’s efforts. Tracy is leading this initiative and advocates for being big and bold with ideas, being brave enough to implement them and never underestimating the impact of small actions. Taking action is a critical key to learning and success. Tracy gave a TED talk titled "Think about what you flush - it has amazing potential!" - click here to see it!

Background on the St. Cloud Public Services Department, from the City of St. Cloud website:

by Nancy Porter, Co Chair, LWV UMRR ILO and LWV Representative to MRN THE MISSISSIPPI RIVER NETWORK (MRN) Annual meeting was held in Memphis, Tennessee on October 24, 25, 26, 2023. The LWV Upper Mississippi River Network InterLeague Organization which represents local leagues from Iowa, Minnesota, Wisconsin and Illinois, (and currently working with Missouri) is a member of the MRN with sixty-eight (68) other groups across the nation. These member groups include Sierra Club, American Farmland Trust, American Rivers, National Wildlife Federation, Friends of the Mississippi River, Iowa Environmental Council, Tulane Institute on Water Resources Law & Policy, among many others. Our representation has grown from forty member organizations to the sixty-eight (68) current members since I have been your representative beginning in 2019. (Covid was a bleak time for all of us.) Because you belong to the LWV, you are also a member of the LWV UMRR-ILO. Our local LWVJC joins the UMRR-ILO for a $25 annual fee. MRN’s policy goal is to advance federal and state policies that promote, just, equitable, and resilient communities through: protecting and restoring ecosystem form and function, reducing impacts of agricultural and urban runoff pollution, and defending bedrock environmental legislation. At our annual meeting we plan for the upcoming year including policy and engagement and involvement and development. We hear from the MRN staff about their equity work and discuss the equity issues in our communities. We discuss and approve the 2024 policy priorities, learn about federal funding and get an update on the Mississippi River Region Initiative. We discuss education and outreach details for 2024 (the following year) and how one can participate. I have been an active member of the Engagement Committee since joining the MRN. We are fortunate to have Michael Anderson as our leader and monthly facilitator at our committee meetings. Vibrant Kelly McGinnis is our official CAO. She began the meeting this year by stating we were in need of some changes to meet new challenges. Last year we added a director of fundraising, Gretchen Hagle, Development Director. Maisah Khan is our enthusiastic and knowledgeable Policy Director. She leads through Farm Bill discussions and and actions and directs policies that promote just, equitable, and resilient communities including reducing impacts of agricultural and urban runoff pollution. Today we took a field trip on the Mississippi River by the banks of Memphis on the Island Queen. We went around Mud Island and watched two barges float by pushed by a tow boat. We went under four of the bridges that cross the River in Memphis. Two bridges were for railroad trains and two bridges were for cars.

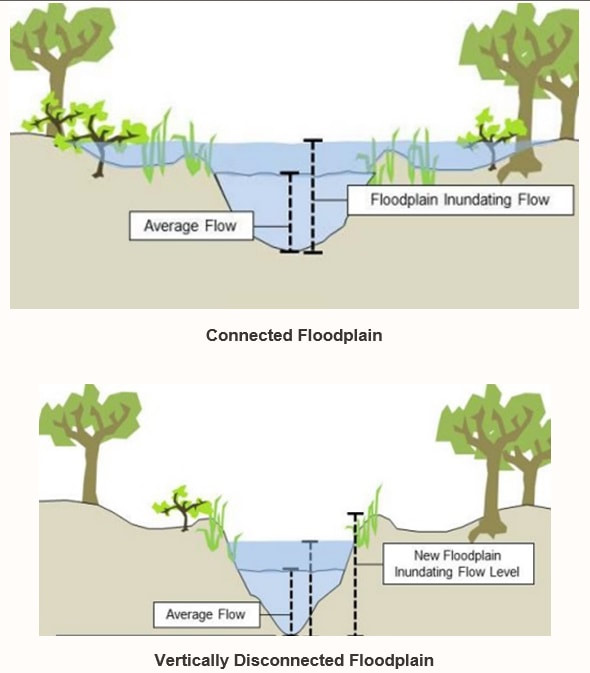

Last night we dined at a Brewery and had plenty of time for great visits with our colleagues. Games of Corn Hole and walks down Beale Street while jazz music filled the air, were part of the evening while we networked and learned from each other. Most of our brainstorming is done in small groups or pairs to generate and records our ideas. Our meeting concluded with a steering committee meeting directed by Maisah. We are full of new information and a mission to increase membership, raise funds so we can continue to develop new ideas and people to protect and sustain our Mississippi River. We have new direction for our Mississippi Days of action and celebrating the River. Our goal is to bring in more groups and create educational opportunities to allow for better understanding and more interaction. The Mississippi River is truly America’s River. It is the third largest River in the world, it furnishes drinking water for over 20 million people, it is a diverse habitat for wildlife, and the backbone of our economy. Along with weak reinforcement of water laws, land pollution from farms, factories, fertilizers, and untreated sewage our great River is in decline. Together, we can protect the River for future generations. This is an article from a recent newsletter from the Anoka Conservation District (ACD), in the Twin Cities area in Minnesota. Thanks to the ACD for their permission to share this article. Beavers Connecting Rivers to Floodplain Wetlands By Breanna Keith, Water Resources Technician, Anoka Conservation District During a recent site visit to explore wetland restoration opportunities, ACD staff came across a fantastic example of beaver's “engineering” skills in action! A series of three beaver dams, located near the outfall of a Rum River tributary, were effectively slowing and spreading the stream’s flow into the surrounding floodplain wetlands. Healthy connections between streams and their floodplains provide numerous water quality and habitat benefits, and in this case those benefits also extend to the Rum River immediately downstream. Many streams, in modified landscapes, take on excess water from artificial drainage features like ditches and storm pipes. Over time and especially during extreme precipitation events, these higher volumes of water often increase erosion within the stream, which can lead to the straightening and downward-cutting (“downcutting”) of the stream channel and, as a result, the disconnection of the stream from its floodplain (see the figures below, produced by American Rivers). Floodplain reconnection efforts are an increasing priority amongst many conservation organizations, but they can be costly and complicated – particularly if development has occurred within the floodplain. However, in areas where streams have room to spill into their floodplains, allowing and even promoting beaver activity can be a very cost effective way to help restore riparian corridor. Parks Canada's website has a wonderful piece about the benefits of beavers HERE. They list five big benefits that beavers impart with their engineering and hydrologic modification.

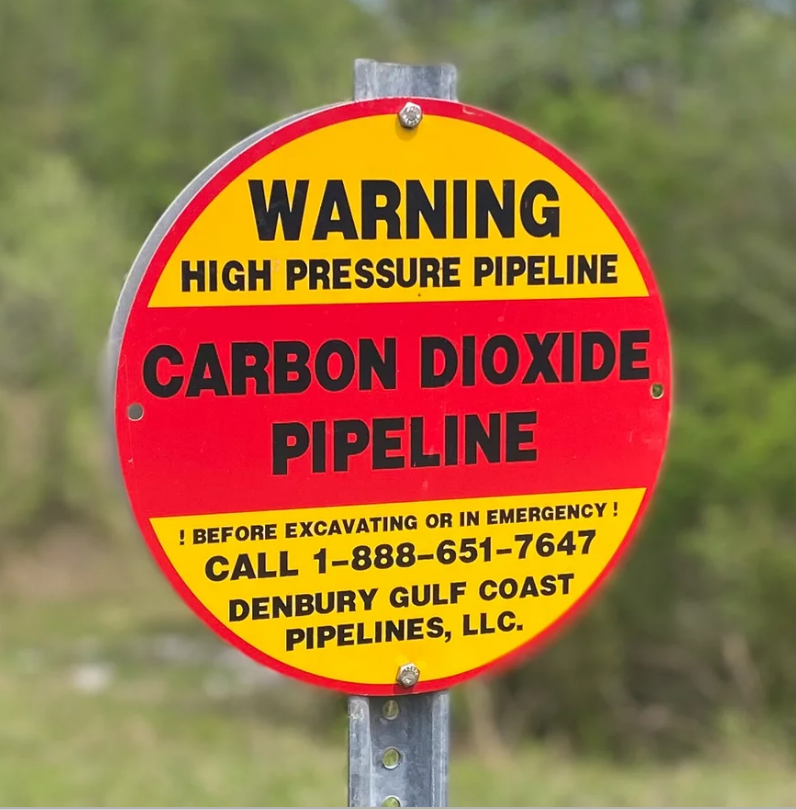

CO2 pipeline companies are having limited success in getting the land easements and permits they need to complete their projects. The EcoJustice Collaborative in Illinois reports regularly on CO2 progress in their blog -check it out at this link. Pam Richart from EJC will be a panelist on Dec 4. She cofounded the Coalition to Stop CO2 pipelines in January, 2022. Since that time, she has been leading the campaign to stop CO2 pipelines throughout central Illinois. The coalition includes 13 organizations, and hundreds of active landowners along the pipeline route. The Coalition’s campaign includes education of landowners and elected officials that has led to the adoption of resolutions and moratoriums in impacted counties, and intervention before the Illinois Commerce Commission (ICC), which is where the pipeline can be stopped. The Coalition maintains a website that documents progress of the campaign, as well as includes resources for landowners, including webinars prepared by the Coalition. In Iowa, the Sierra Club has taken the point in statewide work on the CO2 pipelines. Updates are posted on their website here. In October of 2022, we had Jess Mazour speak on pipelines - you can view the video of her talk at this post on the UMRR blog. On December 4, we will host Jan Norris, an activist from Montgomery County, Iowa, who will report from the frontlines of local pipeline opposition. CURE has been following pipeline progress in Minnesota, and leads action through their project, Carbon Pipelines Minnesota. This webpage has information on current events in Minnesota. Several of the pipeline projects are intended to transport CO2 from Iowa and Minnesota to North Dakota. North Dakota denied Summit's permit application in August, it's now being reproposed. This article on the Associated Press website says: [The North Dakota utility regulators} last month unanimously denied Summit a siting permit for its 320-mile proposed route through the state, part of a $5.5 billion, 2,000-mile pipeline network that would carry planet-warming CO2 emissions from 30-some ethanol plants in five states to be buried deep underground in central North Dakota. Supporters view carbon capture projects such as Summit’s as a combatant of climate change, with lucrative, new federal tax incentives and billions from Congress for such carbon capture efforts. Opponents question the technology’s effectiveness at scale and the need for potentially huge investments over cheaper renewable energy sources. The panel denied the permit due to issues the regulators said Summit didn’t sufficiently address, such as cultural resource impacts, potentially unstable geologic areas and landowner concerns, among several other reasons. The pipelines would pass through South Dakota, which also denied Summit Pipeline's permit application. This September 11 2023 article on the Associated Press website states that the South Dakota Public Utilities Commission unanimously turned the request down. Without access to the North Dakota CO2 depository, the pipeline projects have to keep redesigning their projects. Why are carbon pipelines being proposed? Why are investors and the federal government putting money into these projects? We know that carbon in our atmosphere is causing the earth to warm, which will disrupt our climate and all life on earth. Reducing or eliminating carbon emissions is critical, and there are many different ideas about the best ways to do it. One controversial approach we've been taking for the past two decades is to switch from fossil fuels to 'biofuels' - ethanol and biodiesel. In this post on the UMRR Blog, we reported on a February 2022 report that looks at the utility of ethanol as an option for reducing carbon emissions. The ethanol industry is seeking ways to improve its environmental performance, especially as relates to carbon emissions. One way to do this is to capture the carbon that is released into the atmosphere. The pipelines would move the captured and compressed CO2 to eventual storage and/or reuse. The first two short YouTube videos following provide some more background on why the ethanol industry sees carbon capture as a way forward. The third is a video that provides more information on the process of capturing carbon from industries.

Carbon capture is part of President Biden's climate plan. This link goes to an article in the MIT Review interview with Shuchi Talati, chief of staff at the Department of Energy's Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management. Here, Talati talks about the need to have a range of processes for reducing carbon. We have included a number of references at the end of this post that provide more information on pipeline technology and DOE work on carbon capture. Carbon pipelines are currently used in Texas to transport CO2 for use in extracting oil from spent oilfields, there are also links to information on this practice.

Above, exterior of Giiwedinong, LWV Park Rapids members Beth Baker-Knuttila and CC White at sign, entry murals, Lake Itasca (start of the Mississippi). photos by Gretchen Sabel This museum will bring indigenous culture and history to northern Minnesota. Winona LaDuke told Minnesota Public Radio news, "“This is not a tribal museum,” explains LaDuke, a member of the Mississippi Band of Ashinaabeg. “This is an Indigenous museum, but it is off the reservation. It received no state funding, it's entirely independent. We think of ourselves as the little museum that could.” Click here to read an article on the museum's purpose and work from the Giiwedinong October 2023 newsletter. The museum is built to be an educational resource for Native and non-Native people alike, gearing up for field trips and other educational events. Here's a link to a story from The Circle about the Museum. Here, Winona LaDuke says, “Many people who want to learn about citizen engagement, regulatory processes, treaty rights, and the history of Minnesota will be pleased to come to Giiwedinong." The museum features a gallery that will exhibit the work of Native artiists - the first exhibit is the work of Rabbett Before Horses Strickland, an Anishinaabe member of the Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians of northern Wisconsin. His works depict the Naniboujou and the origins of the Anishinaabe people. This gallery will host a rotating series of Native artists.

From the museum's website: Giiwedinong will be a destination location for all interested in the history of this land, settler and native agreements, treaties, and the waters. We will feature both historic exhibits and emerging artists for our youth, elders and communities. In 2022, Akiing.org, an Anishinaabe-led restoration and community development organization purchased the former Carnegie Library, turned Enbridge office to create a Museum of Culture and Treaty Rights in downtown Park Rapids, Minnesota. Giiwedinong is the first museum of its kind to share the treaties, stories and education of the Deep North, spanning from Wisconsin, Minnesota, North and South Dakota, and beyond in Turtle Island. We recognize, uplift, and promote both emerging and established Anishinaabe artists in their diverse storytelling mediums. We recognize that in order for art to be accessible, we need to bring it out into the community and provide space for art in our everyday lives and promote access internally (for our Anishinaabe people) and externally (as a tool for racial and social justice). We are interested in dialogue and education on these critical issues of the intersections of Indigenous peoples, environment, public policies and fossil fuel economies. Giiwedinong is led by a team of Indigenous historians, artists and community members. Above, LWV UMRR Communication Director Gretchen Sabel with Sarah Littleredfeather at Giiwedinon, MIssissippi Headwaters, celebration of Giiwedinong opening (photo credit #3 to Beth Baker-Knuttila)

Our December 4, 2023, Educational Webinar focused on the lived experience and activism of three extraordinary women committed to educating communities, environmental groups, non-profits, landowners and individuals about the dangers of CO2 Pipelines and carbon sequestration. This was an informative 90 minute presentation on how grass root activism, coalition building and legislative strategies work to stall and ultimately stop CO2 Pipeline development.

For more background on CO2 pipelines, check out this post on the UMRR Blog.

Our guest speaker was Rob Lee, staff attorney for Midwest Environmental Advocates (bio below). Rob provided a brief history of the Clean Water Act (CWA) prior to 2015 regulations defining Water of the US (WOTUS), and the 2020 Navigable Water Protection Rule. Then he'll talk about the May 2023 Supreme Court Ruling and the now revised regulations just issued by US EPA and the Corps of Engineers with a final revised definition of Waters of the US. Once Rob has set the stage, LWV UMRR's Gretchen Sabel will present information on the status of wetland regulation in the UMRR states based on a 2022 analysis by the Environmental Law Institute, followed by a look at LWV positions that relate to actions supporting strong implementation of the CWA. We'll round out the hour with discussion period led by LWV UMRR Chair Mary Ellen Miller. You'll find more information on the Sackett decision here and here on the LWV UMRR blog. Here's a link to an excelllent blog article by Jared Mott of the Izaak Walton League that also provides background. LWV UMRR Board members are engaged and active people who are leaders in other organizations besides LWV and speak out about issues affecting water and climate! This column by Kay Slama, LWV UMRR Board member, is an opinion piece originally published in the Lakes Area Review, New London MN in August, 2023.  Carbon dioxide (CO2) pipelines carry highly compressed (supercritical) CO2. The proposed Summit Carbon Solutions pipeline would run through southwest MN, carrying CO2 from ethanol plants to North Dakota to be buried underground. The federal Infrastructure Act and Inflation Reduction Act give credits for carbon sequestration, awarding our tax dollars for private companies to build carbon pipelines. Because it would keep carbon out of the atmosphere, you’d think this would be a good thing, right? But wait—there are loads of problems with carbon pipelines, see www.carbonpipelinesmn.org and www.carboncapturefacts.org. The North Dakota Public Service Commission denied Summit’s siting permit application for underground sequestration, citing many issues that the company had not addressed adequately. Until ND allows the pipeline, the MN Public Utilities Commission should pause its permitting for the pipeline, since there’s no place for the CO2 to go. Unfortunately, on August 31, the PUC refused to make that reasonable decision, and we need to let them know that was unwise for Minnesota. What about human safety? CO2 is an asphyxiant—it keeps our lungs from getting oxygen when we breathe. CO2 pipelines must be pressurized at three times the rate of a natural gas pipeline (1,200-2,800 psi). Ruptures can occur for a number of reasons. One cause of ruptures can be shifting ground, whether from flooding or the ground sinking as water is used for irrigation. According to the Pipeline Safety Trust, many chemical impurities can get into the line. Any water molecules in the pipeline react with CO2 to form corrosive carbonic acid. Ruptures have occurred in carbon pipelines, causing human and animal deaths. CO2 is heavier than air, and its unpredictable flow depends on terrain and changing weather. Without wind, it may just find low spots and sit there for a long time. National Public Radio and other media reported on a pipeline rupture in Mississippi that caused 45 people to be hospitalized. It kept cars and emergency vehicles from working because combustion engines need oxygen. Emergency responders need breathing apparatuses that cost more than $6,000 apiece, so they would have to call in a specialized hazardous materials team. The planned carbon pipeline routes run close to homes, towns, and schools, so the CO2 plumes could reach them. The federal agency responsible for CO2 pipeline standards is reviewing them in light of the dangers. These are more reasons construction of carbon pipelines should pause while safety is being worked out. Land issues need to be considered with carbon pipelines. Installation compacts a wide swath of soil that is almost impossible to loosen so roots can get into it. The pipelines heat land near 90 degrees, and both resulting evaporation and heat make it harder for plants to grow. Restoring soil health and productivity is a long-term struggle both current farmers and future generations will have to bear. There are many stories about Summit bullying landowners and using misinformation to obtain easements across farm property. Easement payments to farmers last 3 years, but the easements are permanent, so landowners are vulnerable to other uses after the 20-25-year life of the pipeline. Pipelines tend to be abandoned in place after they are no longer useable, so they remain a permanent hazard on the property and its underground water flow. Iowa is considering using eminent domain to run CO2 pipelines through farmers’ lands without their consent. Under the Fifth Amendment, eminent domain must be for a “public use,” which traditionally meant projects like roads or bridges, not the enrichment of private corporations. In the big picture, pipelines encourage growing huge amounts of corn in the US, nearly half of which is used to produce ethanol. This discourages growing alternate crops that may be better for our land, need less fertilizer and irrigation, and send less pollution down our rivers and into our lakes. Next are water issues. The buried carbon pipelines cross rivers and wetlands underground, which can puncture aquifers during construction, as we saw with the Enbridge Line 3 pipeline in northern MN. In addition to water used during construction, the pipelines will require 13,000,000 gallons/per facility using the pipeline per year (from Summit’s response to inquiry on water usage during Minnesota PUC 5/4/2023 scoping meeting). This constitutes a risk of drawing down our lake and river levels and aquifers. Energy issues: Much energy is needed to mine materials for carbon pipelines, which must be much thicker than any other kind to contain so much pressure. Much fuel is required to put the pipelines in the ground. Energy sources process the gases and condense CO2 at its sources, as well as run the pumps and bury the carbon. There is evidence that making ethanol out of corn is a life-cycle process that may use more CO2 than it saves. We have alternative land-use programs that encourage natural plants which sequester CO2, as well as encourage more wildlife and pollute less. On top of that, a ND official admitted that pipeline CO2 will be used to compress fossil fuels out of the ground, a process known as fracking, which will put more CO2 in our atmosphere and cause more of the climate change effects we’ve been seeing so much lately. So what can we do? We need to think ahead for our climate and our agriculture. We should be spending our “public” money on helping farms move away from growing so much corn. Help farmers feed people rather than make carbon-intensive ethanol, and help them diversify. We need to create markets in MN for their crops. It will take regular input to our lawmakers and state agencies to help them act with this future in mind. We need to do all we can to address the excess carbon that is warming our planet and causing global climate change. Carbon sequestration may indeed be one of the solutions, but not by crisscrossing our land with potentially unsafe pipelines that will threaten our land and waters and almost certainly lead to fracking for more fossil fuels. We need to focus on making our climate better, not worse. Water is a big topic these days! Here's a round up of stories from around the Upper Mississippi Basin From the Freshwater Society: U of MN and Freshwater researchers to evaluate injection wells, infiltration basins. With groundwater shortages becoming a concern in some areas of the state, researchers at the University of Minnesota and Freshwater will be poised to assist by deploying a first-of-its-kind GIS mapping tool that could help pave the way for managed aquifer recharge in Minnesota. From the Daily Memphian: As Mississippi River levels swing between historic highs and lows, shipping industry grapples with how to adapt Right now, drought is the one consistent condition along the length of the river. The Mississippi has reached near-historic lows for the second year in a row, which is slowing down shipping and driving up costs for everyone from barge companies to grain elevators. From MinnPost: Warming urban aquifers become fermentation vessels for water-borne pathogens, providing one more reason why replacing aging infrastructure is a good idea. From the New York Times: Big Farms and Flawless Fries Are Gulping Water in the Land of 10,000 Lakes. When Minnesota farmers cranked up their wells in a drought, they blew through state limits. Thirsty crops included corn, soybeans and perfect, fry-friendly potatoes. From Chris Jones' Substack: Honk if you smell BS... said the gander. Iowa's Lake Darling is full of algae... who's to blame? Is it the geese? From Circle of Blue: Chicago Suburbs, Running Out of Water, Will Tap Lake Michigan. The project is a reminder that even in rainy places that seem most water-secure – the shores of the Great Lakes, the Mississippi River basin – a reliable supply is not always assured. From the River Alliance of Wisconsin:

Little Plover River Flows Less than “Healthy” for Two Months, High Capacity Wells Blamed. Once again, the Little Plover river is in trouble, and not only because of this summer’s drought. To understand why the Little Plover isn’t flowing like it has been in the past few years, we have to look underground. |

| LWV Upper Mississippi River Region | UMRR blog |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed