|

Join LWV UMRR for a panel discussion on Zoom - August 15, 2024 at 7pm. Salt is a big problem for streams, lakes and rivers in the Upper Mississippi Basin. Salt - sodium chloride - breaks down into sodium, which is absorbed on soils, and chloride, which moves freely through soil and builds up in water bodies. (Read more about trends in chloride in this post!) Once salt goes down on roads or sidewalks, it doesn't go away. Salt levels are rising in lakes, streams, and rivers in Illinois. Overuse of salt during the winter can damage our built and natural environments. We can protect our natural resources and reduce road salt without sacrificing safety. Working towards better practices is a multi-faceted endeavor. Programs like the Salt Smart Collaborative, a program of The Conservation Foundation, encourage the use of Salt Smart practices in winter maintenance operations. Salt Smart practices are the best practices for winter maintenance operations that reduce salt use and provide safe surfaces. Resources (like workshops and trainings, the Salt Smart Certified program, and targeted outreach materials) are made available through the Salt Smart Collaborative to transportation agencies, municipalities, park districts, and private contractors to encourage and support the adoption of the best practices for salt use. This event on August 15 will help us to build our understanding on this important topic in water quality! This graphic from the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency shows the sources of salt (chloride) in the environment. States like Minnesota, Wisconsin and Illinois have programs to address chloride, and in our upcoming program on August 15, we will hear about these programs. Our speakers will be Hannah Miller, Watershed Program Manager with The Conservation Foundation in Illinois; Allison Madison, Manager of the Wisconsin Salt Wise Program; and Brooke Aslesen, Watershed Specialist with the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency. This panel will share information on salt managment programs in their respective states, which will provide a background for understanding this topic. Both the Minnesota and Wisconsin legislatures had bills on salt management in the 2024 sessions. It is important for advocates to understand the background of currrent practice as we move into the 2025 session. The Minnesota bill (HF3565 and SF3954) died in the 2024 legislature, and Governor Evers vetoed the Wisconsin bill (Senate File 52). Background and References: LWV Duluth Environmental Action Committee Meeting & Izaak Walton League January 17, 2024 "Putting Duluth on a Low (Road) Salt Diet" Click here to view the recording of this presentation This recording features a panel of three speakers from New Hamshire, which has implemented a salt program which is a model for other states. UMBRA Report on Mississippi River Water Quality (Upper Mississippi River Basin report) Decades of Road Salting Is Polluting the Mississippi River (Milwuakee Journal Sentinal) The Impact of Road Salt on Local Waterways (Wisconsin legislation) SPEAKERS FOR THE AUGUST 15 EVENT: Hannah Miller, Illinois Allison Madison, Wisconsin Brooke Aslesen, Minnesota Hannah Miller, The Conservation Foundation Hanna Miller is a Watershed Project Manager at The Conservation Foundation working on reducing the impacts of chlorides. She is the workgroup coordinator for the Chicago Area Waterways Chloride Workgroup and the co-coordinator for the Salt Smart Collaborative. Hanna graduated from Hamilton College with a degree in Geoscience. Outside of work, Hanna can often be found cycling along one of the many waterways in the Chicago area. Allison Madison, Wisconsin Salt Wise Program Allison Madison is the Wisconsin Salt Wise Program Manager. Since assuming her role in June 2020, she has spearheaded collaboration around salt reduction in watersheds across the state. Her work takes her to mall parking lots, urban streams, County Highway shops, and the Capitol building. Allison has 10+ years of experience in science and sustainability education in both formal classrooms and National Parks. Allison graduated from St. Olaf College and has a joint MS in Environment and Resources and Soil Science from the University of Wisconsin. She's passionate about protecting Wisconsin's freshwater resources and celebrating their beauty by paddling, swimming, cross-country skiing, etc. Brooke Aslesen, Minnesota Chloride Reduction Program

Brooke Aslesen has worked at the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency since 2007 where she works collaboratively with federal, state, local partners, and research institutions to protect Minnesota’s water resources. She has been working on chloride and water quality issues at the MPCA for over 16 years. The core of that work has been developing partnerships with a wide variety of experts and professionals to develop strategies that reduce chloride while supporting public needs. Brooke now coordinates the MPCA’s Chloride Reduction Program that includes the highly successful Smart Salting training program as well as the new Chloride Reduction Grant program, the Smart Salting Tool and many other resources to help communities and organizations reduce salt use and protect Minnesota's water resources. Brooke earned her Master’s degree in Water Resources Science from the University of Minnesota. Her undergraduate degree is in Environmental Science with a minor in Soil Science also from the University of Minnesota. Prior to attending graduate school, she worked in the Metropolitan Council’s Metro Wastewater Treatment Plant lab. Recent scientific advances have facilitated exploration of the microbiome and are spurring interest in how microbial communities are connected among species and how attention to microbiomes can support soil health, food quality, and human health. There is also the possibility that new discoveries in the soil microbiome could facilitate drug development and address threats to human health, including antibiotic resistance, contaminants, and soil-borne pathogens. Finally, there are questions about whether management practices are linked with the nutrient density of the food produced and about the interactions of the soil microbiome with soil contaminants. Therefore, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture asked the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to convene a committee of experts to explore the linkages between soil health and human health (see Figure 1). The committee approached its task from a One Health concept, which posits that soil should be valued as an ecosystem that, when healthy, contributes to the health of other ecosystems, plants, humans, and other animals. Here are the highlights of their June 2024 report. These notes were prepared by LWV UMRR Board member Mickey Croyle (LWV St Louis, MO), based on a webinar given by the National Academy of Sciences on June 13, 2024. To obtain a copy of the full report, click here. The graphic above was used to show relationship and need to study throughout then presentation USDA, Food and agriculture funding paid for the report to look at human health, animal health, soil, environmental heath and define the relationship for soil and human health. The mycobiome needs to be studied in greater detail. The soil biodiversity in mycelium (fungus) and microorganism is implicit in this aspect. DNA sequencing is getting better understanding. Healthy soil with intact microbiome affects animal and human gut microbiome. Soil health correlates to people: - food supply - nutrient quality - water requirement and supply - suppression of disease LINKAGES BETWEEN SOIL MICROORGANISMS AND HUMAN HEALTH The most obvious linkage between soil microorganisms and human health rests on the fact that soil microorganisms do the work needed to produce food, including cycling nutrients and carbon, filtering water, and building soil structure and organic matter. Perhaps less recognized is the critical role the soil microbiome plays in climate regulation, including carbon sequestration, and the ability of soil microbes to metabolize many organic contaminants into harmless byproducts, which limits exposure to humans. We need to advance our understanding of linkages between soil microorganism and human health: - more robust sampling with enhanced data re-utilization that will quantify the microbial roles in human and soil health - improved decoding and diagnostic platforms to more effectively monitor the heterogeneity and dynamics in microbiomes - support cross domain collaboration to prove an integration microbiome understanding that spans the soil to human continuum. LINKAGES BETWEEN AGRICULTURAL MANAGEMENT PRACTICES AND HUMAN HEALTH Common agricultural management practices have increased crop yield and food security, but this productivity has often come at the expense of soil health, with detrimental effects on the environment and human health. For example, synthetic fertilizer use has greatly increased crop production but also caused excess nutrients to leach from agricultural fields, sometimes resulting in contaminated groundwater, algal blooms, and production of potent greenhouse gases that contribute to climate change. At its most fundamental level, agricultural management practices often create trade-offs between the many services soils provide to people; for example, food production on the one hand and, on the other, the ability of ecosystems to sustain biodiversity, sequester carbon, and perform myriad other functions that are equally, even if less obviously, essential to human health. Nutrient availability in the soil and environmental conditions, management practices and plant genetics all participate in determining nutrient density in the food supply. Pre-quality and post harvest variables also affect nutritional quality of food consumes. This makes it difficult to identify direct linkages from soil health to crop nutritional quality and effect on human health - Food composition -food processing - foodborne pathogens mycotoxins - consumer food choices LINKAGES BETWEEN AGRICULTURAL MANAGEMENT PRACTICES AND THE NUTRITIVE VALUE OF FOOD Although there is a common perception that healthy, well-managed soils produce healthier foods, the connection is not always clear. Nutrient availability in the soil, environmental conditions, management practices, and plant genetics all play a part in determining the nutritional quality of food. Comparative studies of different production systems (e.g., conventional versus organic) have tried to assess the interplay of these factors, but variations in experimental design, soil types, crop species, and environmental conditions have yielded divergent results. What ultimately determines the nutritional quality of food crops is the amount of essential nutrients with health-promoting potential that are transported to, or synthesized within, the edible portion of the plant. These include minerals and biosynthesized macromolecules such as amino acids/proteins, carbohydrates, lipids, vitamins, and phytochemicals. We need to advance understanding of linkages between agriculture management practices and the nutritive value of food requires: - translation research to understand the effect of practices on nutrient and bioactive density of crops - Research to understand how food composition can be influenced by management or breeding to achieve higher levels of health beneficial compounds - Research to understand the utility of bio stimulants in nutrient uptake and yield and potential effects on indigenous soil - Research in food processing technology that enhance profile of health beneficial nutrients and compounds. IMPROVING SOIL HEALTH TO IMPROVE HUMAN HEALTH A healthy soil sustains biological processes, decomposes organic matter, and recycles nutrients, water, and energy, reducing the need for synthetic fertilizers and irrigation. It helps mitigate exposure to some chemical contaminants and sustains food production. All of these functions make the prioritization of soil health for human health benefits even more important in the face of climate change, which will adversely affect soil nutrient cycling and exacerbate the detrimental effects of flooding or drought on soil stability and water-holding capacity. Improving soil health to improve human health needs: -better quantification of soil health using a national monitoring approach - more long term and on the farm research to better understand the underlying mechanism of soil health - research into management practice that overcome potential trade offs from common agriculture practices -research that increase the safe and effective use of underutilized resources - investment in plant breeding fro more complex systems - Farm program support for practices that impove soil health and increase crop spatial and temporal diversifications. GOING FORWARD Shifting the perception of soil to a valued ecosystem that is interconnected with the health of plants, humans, and other animals will be spurred on by a better knowledge of underlying mechanisms contributing to soil health and its connectedness to plant and human health, and a continued optimization of ways to quantify and compare health. It will require changes in farm-support programs to value soil health as a metric of success and to transition toward more complex and perennial cropping systems as well as increased circularity where waste streams are turned into safe resources. Finally, societal awareness of the role soil health plays in human health beyond food production must increase, which will require the involvement of many federal agencies, scientific societies, companies, and international organizations. We need to increase awareness of relation health and soil. Federal agencies and scientific societies should continue their work to promote the public awareness of the importance of soil health and societal value beyond the immediate material benefits: Interrelationship between the build environment, water habitat wild animals, humans soil and plants, air, land. COMMITTEE ON EXPLORING LINKAGES BETWEEN SOIL HEALTH AND HUMAN HEALTH Diana H. Wall (Chair), Colorado State University; Katrina Abuabara, University of California, San Francisco; University of California, Berkeley; Joseph Awika, Texas A&M University; Samiran Banerjee, North Dakota State University; Nicholas T. Basta, The Ohio State University; Sarah Collier, University of Washington; Maria Carlota Dao, University of New Hampshire; Michael A. Grusak, U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Research Service; Kalmia E. Kniel, University of Delaware; Ylva Lekberg, MPG Ranch; University of Montana; Rebecca Nelson, Cornell University; Kate M. Scow, University of California, Davis; Ann Skulas-Ray, University of Arizona; Lindsey Slaughter, Texas Tech University; Kelly Wrighton, Colorado State University

STUDY STAFF Kara N. Laney, Study Director; Roberta A. Schoen, Director, Board on Agriculture and Natural Resources; Ann L. Yaktine, Director, Food and Nutrition Board; Katherine R. Kane, Senior Program Assistant (through March 2024); Samantha Sisanachandeng, Senior Program Assistant (from April 2024) FOR MORE INFORMATION This Consensus Study Report Highlights was prepared by the Board on Agriculture and Natural Resources based on the Consensus Study Report Exploring Linkages Between Soil Health and Human Health (2024). The study was sponsored by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of any organization or agency that provided support for the project. Copies of the Consensus Study Report are available from the National Academies Press (800) 624-6242 | https:// nap.nationalacademies.org Division on Earth and Life Studies

In this video, our speakers talked about watershed restoration and how natural infrastructure is so much more effective at flood control than constructed dams, impoundments and hardscapes. An interesting Q&A followed, moderated by Jenny Whidden, Climate and Environment reporter from the Daily Herald and brief remarks by Illinois State Senator Laura Ellman, author of recent legislation to protect Illinois wetlands left unregulated by the Sackett decision. Each speaker started out by discussing their journey to becoming a water resource professional and the watersheds they are tied to. The organizations represented in this event, and the people who represented them: LWV UMRR - Gretchen Sabel, Communications Director DuPage County Stormwater Division - Sarah Hunn, Director, DuPage County Stormwater Management Forest Preserve District of DuPage County Eric Neidy, Director of Natural Resources SCARCE - Kay McKeen, Founder and President Above: Sarah Hunn, Kay McKeen and Eric Neidy

With help from a grant from the Mississippi River Network, LWV UMRR and artist Christine Curry will be showing up at venues up and down the river with this display. Come and see it when it's in your area! Here's a partial list - sign up to get updates as we travel! Friday, April 12-20: Pure Iowa Water—Pop Art Exhibit Opening Reception Friday, April 12 from 2 to 4 p.m. at the Galena Public Library, Galena, Illinois. Exhibit remains on display until April 20th. For more details, click here. Monday, April 22-23: Pure Iowa Water—Pop Art Exhibit will be at the Musser Public Library in Muscatine, Iowa with a special Earth Day program starting at 6 p.m., Monday, April 22nd. For more details, click here. Wednesday, April 24-25: Pure Iowa Water—Pop Art Exhibit will be at the Environmental Learning Center in Muscatine, Iowa, with a special presentation at Thursday, April 25th at 10 a.m. For more details, click here. Many more dates to come, from St. Paul to St. Louis! Sign up to get updates and come see the exhibit when it comes to a river town near you! May 29 at 7pm - Join LWV UMRR as we host Riverlorian Steven Marking!

*A Riverlorian is defined as follows: "One who studies rivers and shares all aspects of navigation, nature, history, legends & lore with anyone who will listen. This could expand into river related topics that interest the Riverlorian and possibly even the audience."

Mary Ellen and brother David, a few years ago Mary Ellen and brother David, a few years ago The Nishnabotna is a river in southwestern Iowa. It starts in Carroll County, Iowa, and flows south, entering the Missouri near Watson, Missouri. The predominant land use in the area is row crop agriculture. Small cities along the river include many businesses that support agriculture. The West Nishnabotna is a designated water trail and outfitters will set folks up with kayaks and tubes to enjoy the river. LWV UMRR Chair, Mary Ellen Miller, was born in Red Oak, Iowa, a small town on the banks of a small river, the East Nishnabotna. She remembers standing on her porch as a small child, watching the flooded river lapping at the steps of her family home. The river flooding was exacerbated by removal of wetlands and natural ponding, and straightening of the meanders that used to hold water upland. The Nishnabotna is a very different river than it was before Europeans arrived on the prairie. The Spill: On March 11, a massive spill of liquid fertilizer from the NEW Cooperative in Red Oak was discovered. Apparently, it had begun on March 9, when a valve was left open and 1500 tons (265,000 gallons) of inorganic fertilizer were discharged into a drainage ditch that flows into the East Nishnabotna. Iowa DNR is investigating. According to the Iowa Capitol Dispatch (3/13/24), "An investigation into the extent of the environmental damage is pending, but the crop fertilizer killed fish and might have affected the river all the way to the Missouri border, which is about 40 miles downstream from the southwest Iowa town, said Wendy Wittrock, a DNR senior environmental specialist who investigated the incident. Wittrock said it is likely the largest fertilizer spill she has investigated: “It is a lot of fertilizer.” The spill was reported Monday morning by NEW Cooperative after one of its employees noticed the leak and stopped it. The cause of the spill is under investigation, but the fertilizer leaked from a valve in an area where it is transferred from a very large tank into smaller tanks for distribution. The large tank — which holds about 500,000 gallons — is in a containment area that can prevent wider spills, but the transfer area does not have the same protection, Wittrock said. It’s unclear how long the valve was leaking. “Upon discovery of the spill, management immediately initiated containment protocols as per our established safety procedures,” NEW Cooperative said in a prepared statement on Wednesday. “We promptly notified the appropriate local authorities and regulatory agencies and have been working diligently in close cooperation with them ever since.” A spokesperson for the Fort Dodge-based cooperative declined to comment further. That amount of fertilizer is worth hundreds of thousands of dollars. Impacts of the Spill: Dead Fish

Dead fish and other river life line the watercourse, all the way to the Missouri River, 60 miles from the spill. The Des Moines Register reports "State conservation officials have found no living fish in the East Nishnabotna River south of Red Oak — the result of a massive fertilizer spill at a farmers cooperative. The only living fish were discovered near Hamburg in far southwest Iowa, downstream of where the river joins with the West Nishnabotna, said John Lorenzen, a fisheries biologist for the Iowa Department of Natural Resources. However, the handful of surviving carp he saw appeared to be in the process of dying. “I’ve never dealt with a situation like this before,” Lorenzen said." In a March 27 article, the Iowa Capitol Dispatch reports that 750,000 fish died in this incident. This number would have been higher except that the fish populations are low at this time due to cold temperatures and low flows. Impacts of the Spill: Drinking Water Risks The DNR alerted towns downstream from Red Oak about the potential effect the spill might have on drinking water, although none of the towns draw water directly from the river. Several of them have relatively shallow wells near the river, according to DNR records. The Iowa DNR is encouraging private well owners near the river in Montgomery, Page and Fremont counties to contact their county health department to test their wells for nitrate. The service is free using Iowa's Grants-to-Counties (GTC) program. Missouri state officials are also investigating the impacts the spill might have on the Nishnabotna River, which goes for about 10 miles in that state before joining the Missouri River. Kansas City draws drinking water directly from the river, but the Missouri River is large and the city is more than 100 miles downstream. “We think it’ll be fairly diluted by the time it gets down here,” said Karen Rouse, a regional director for the Missouri Department of Natural Resources. (Source: Iowa Capitol Dispatch 3/13/24) Impacts of the Spill: Risk to Livestock Because of low water levels in the East Nishnabotna, the concentration of liquid nitrogen fertilizer is higher than normal and causing concern for animals due to high nitrate and urea levels. The Iowa State University College of Veterinary Medicine Toxicologist Scott Radke recommends animal owners keep them away from the river until the fertilizer moves out of the area. (Source: WQAD News, March 13, 2024) ILLINOIS, WE HAVE A PROBLEM! Of the streams that Illinois EPA has assessed for water quality conditions from 2020–2022:

This campaign that aims to change the way Illinois thinks about and cares for its water. Starting in southern Illinois and working their way north, PRN will support downstream communities by listening to their concerns and helping to identify and implement locally-informed solutions and financial resources. Through these efforts, PRN will support communities as they build climate resiliency and advance their vision for the future. Clean Water Forever starts with telling the truth about the water quality crisis in the Midwest and ends with finding long-term solutions to protect Illinois communities. Robert Hirschfeld is the Director of Water Policy for the Prairie Rivers Network. The Prairie Rivers Network is based in Champaign, Illinois.

Illinois’ communities, rivers, and habitat. He also works on many of PRN’s communications and social media campaigns, and he produces videos and podcasts. Background: Robert joined PRN in March 2011. Before joining the professional staff, Robert was a legal intern for PRN, working on Clean Water Act compliance and enforcement. Robert sometimes dabbles in music. Education: B.A. in religion and Asian studies from the University of Puget Sound and a J.D. from the University of Illinois College of Law About the Prairie Rivers Network:

The Prairie Rivers Network works to protect water, heal land and inspire change, using the creative power of science, law, and collective action. Prairie Rivers Network is the independent, state affiliate of the National Wildlife Federation. You can read the PRN 2020-2024 Strategic Plan for more information on their mission and vision for Illinois’ rivers and streams. Here are links to information about PRN's organization: MISSION & HISTORY ACCOMPLISHMENTS BOARD OF DIRECTORS STAFF

It is designed to ignite and spark conversations by using impactful, oversized 2D and 3D advertising graphics and labels on 16 oz aluminum cans that depict the water quality problems in our region by promoting a fictitious sparkling water company that bottles water directly from streams in the watershed. The exhibit also showcases champion conservation farmers that show how better land management can be part of the solution to our dirty water issue. The exhibit includes an inflated oversized pop can labeled as “Pure Iowa Sparkling Stream Water” to appear to be real and legitimate. The back label includes a description of the stream, a reflection, and a list of “natural” ingredients telling a very different story … the many harmful contaminants that are commonly found in many of the waterways throughout the upper Midwest. A red warning label further compounds conflicting advertising messages. There are QR codes providing easy access to relevant links to scientific data, resources and references. Our plan is to travel this exhibit widely and to that end we need each local and state League in the UMRR watershed to identify suitable events, sites and dates to host the display. The site needs to be indoor and have access to electricity. Our first priority is to target primary League events within each state, especially state/local League meetings and events that will draw a crowd. In addition to League events, the exhibit will participate in the 100th anniversary celebration of the Upper Mississippi River National Wildlife and Fish Refuge and the MRN 1 Mississippi annual summer Days on the River events. We are also partnering with the Isaak Walton League to help identify other potential exhibit sites. Grant funding will support the transportation and/or shipping of the exhibit, local exhibit fees and the artist travel costs. Suggestions for possible exhibit locations along with potential dates should be sent to Project Coordinator Mary Ellen Miller at [email protected] 515.783.6390.

The Minneapolis Star Tribune's January 21, 2024 article, Health Checkup for the River, states, "A new report tracks pollution in the upper river and a major tributary. It finds good news on lead, phosphorus and sediments, and troubling trends on chloride, nitrogen and some gaps in data collection." The first and continuing mission of the LWV Upper Mississippi River Region was to work to lessen nutrient loading to the Upper Mississippi. As such, we follow reports like this closely. In this report, the analysis shows that there has been progress in some parts of the river in reducing nutrients, but other areas nitrogen and phosphorus continue to increase. UMBRA summarizes the findings of the report in more detail: Positive Trends

Negative Trends

Data Gaps

Minding the Gaps:

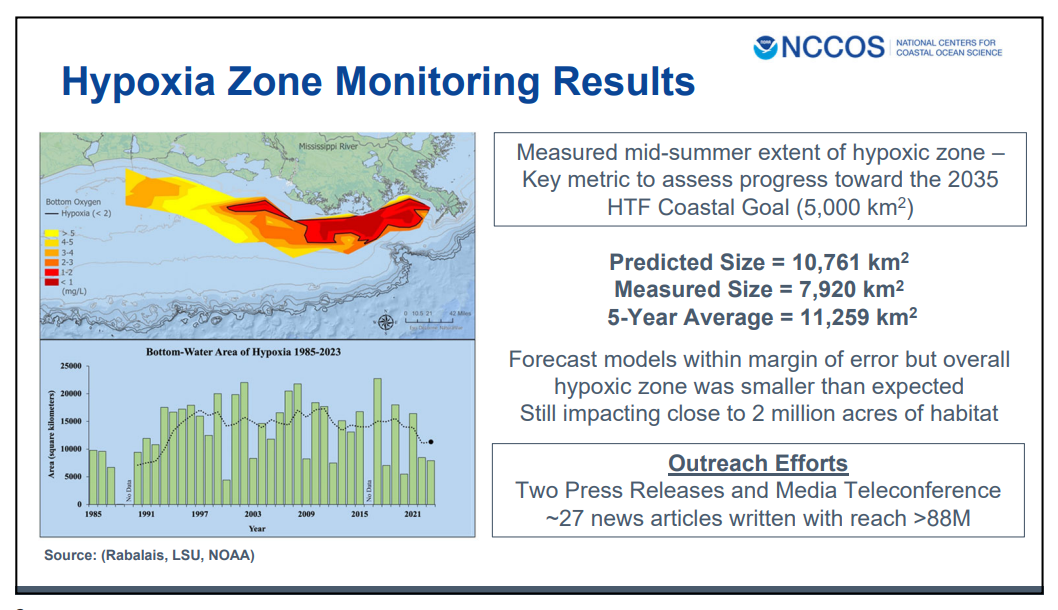

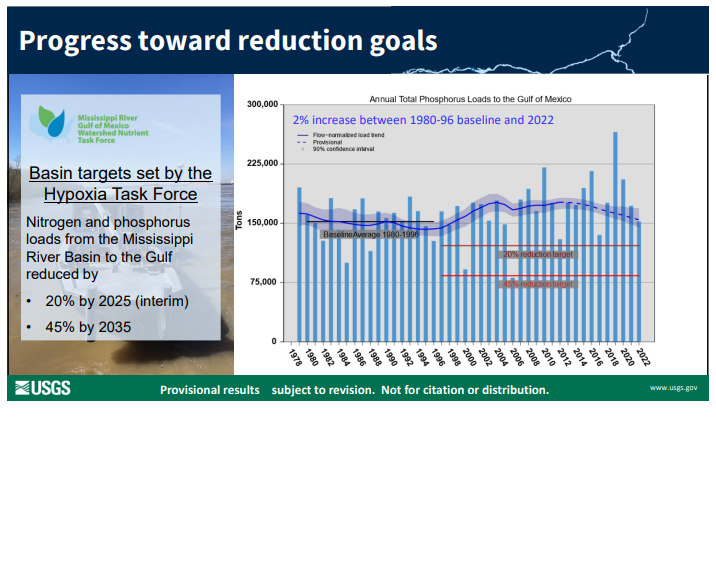

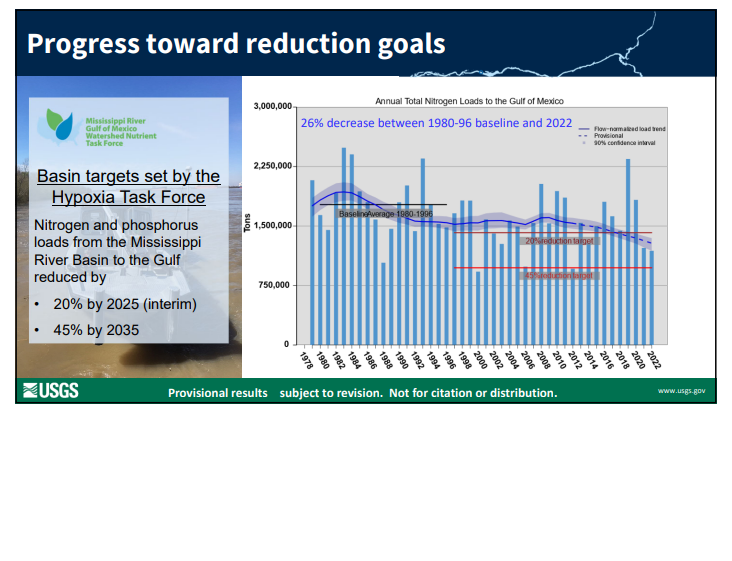

Description of the UMRBA monitoring strategy, from the UMRBA website - "UMRBA's Interstate Water Quality Monitoring Strategy facilitates coordinated and comprehensive water quality monitoring for the Upper Mississippi River. Probabilistic and fixed site sampling are designed to support the states' ability to determine whether Clean Water Act goals are being met related to four major designated uses (aquatic life, drinking water, fish consumption, recreation). ... The states are committed to integrating and utilizing existing program data and information to the greatest extent possible and anticipate working closely with other programs in data sharing. Several federal, state, and regional programs conduct significant water quality monitoring. Those efforts are designed to meet their own objectives, none of which are capable of supporting the states' Clean Water Act (CWA) purposes and that cover the river’s full spatial extent." In 2014, the UMRBA developed a monitoring strategy for the Mississippi River main stem. All of UMRBA's five states are committed to this Interstate WQ Monitoring Strategy, both in terms of supporting the creation of the monitoring plan and securing implementation funding. Although the monitoring is designed to determine whether the mandates of the Clean Water Act are being met, there is not dedicated federal funding to support the monitoring. Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Illinois monitor on the Upper Mississippi River mainstem through their state specific ambient monitoring programs. Iowa and Missouri do not have mainstem monitoring through their state ambient monitoring programs. In 2016-2017 UMRBA piloted the monitoring plan on shared borders between the Twin Cities and La Crosse, Wisconsin. In 2020-2021, the shared borders between Lock and Dam 17 to Lock and Dam 21 (including Iowa, Missouri, and Illinois state agencies) were sampled. UMRBA and the five states are planning to sample its fixed site network on the Upper Mississippi River (12 sites from Lock and Dam 2 to Thebes, Illinois) will be sampled starting October 2025 through September 2026. This will continue implementation of portions of UMRBA’s monitoring plan, but federal funding to fully implement and operationalize UMRBA’s monitoring plan is needed to create long term datasets for the UMR and address current data gaps in monitoring. The Gulf Hypoxia Task Force met on December 6, 2023, in Fayetteville, Arkansas. Here, agencies reported progress on addressing the Dead Zone in the Gulf. For the full report check out the reports here at this link. The graphic above was presented by Dave Scheurer of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The Dead Zone, as measured in the mid-summer survey, was smaller than expected but this was attributed to the drought that gripped the Mississippi River Basin in 2023. Lower flows meant that less nutrients were washed off the land and so less nutrients reached the Gulf. Lori Sprague of the US Geological Survey provided a water quality update in three succinct slides: The Gulf Hypoxia Task Force set a revised goal of lowering Nitrogen and Phosphorus discharges to the Gulf by 20% by 2025 and 45% by 2035. These slides show that as of 2022, Total Nitrogen loads from the Mississippi and Atchafalaya Rivers have dropped below the 2025 goal level but have not yet reached the 2035 goal. Phosphorus remains above the interim level.

|

| LWV Upper Mississippi River Region | UMRR blog |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed